Cave 249 – The Western Wei

The Cave Temple

Constructed during the Western Wei (535-557 CE), Cave 249 is in the palace hall style.1 The west wall has an open niche with a Buddha statue elevated on a platform with two flanking bodhisattva statues. The wall murals depict the Thousand Buddhas, a common symbol found in many cave temples.2 This cave’s standout feature is its ceiling mural, which intertwines imagery from Taoism and traditional Chinese mythology with Buddhist imagery. Worshippers likely used this temple to pay homage and send their offerings.3

Taoist Imagery and Traditional Mythology: A Case Study in the Sinicization of Buddhism

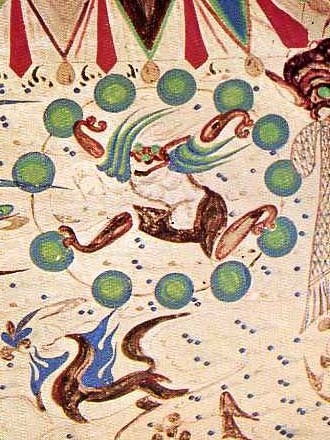

Intermingling with Buddhist imagery on Cave 249’s walls are symbols alluding to another Chinese teaching – Taoism. Of the four sloping ceiling sections, the eastern and western slopes focus on Buddhist elements while the southern and northern slopes portray Taoist features.4 The main deities of the northern and southern slopes are immortals riding in dragon- and phoenix-drawn vehicles, respectively. Many scholars believe these figures represent the Eastern Lord (Dongwanggong) and the Western Queen (Xiwangmu), central Taoist deities who embody yang and yin.5 Both the chariots of the Eastern Lord and the Western Queen are escorted by processions of winged fish, Kaiming (creatures with human heads and dragon bodies), and other celestial animals.6

The mural also incorporates other figures and symbols from traditional Chinese mythology and Taoism. The north, south, and east slopes depict respectively the 13-headed Heavenly Emperor, the 11-headed Earth Emperor, and the 9-headed Human Emperor from the novel Shi Yi Ji.7 The west slope includes nature gods, such as the Thunder God and Lightning God. The nature gods pictured are explicitly traditional Chinese depictions, not Buddhist. For instance, the wind god is depicted as horned and beast-headed, resembling his form in traditional Chinese mythology and not any Buddhist deity.8 The four Taoist guardians of the cardinal directions (Phoenix of the South, Black Tortoise of the North, Blue Dragon of the East, White Tiger of the West) all feature on the walls corresponding with their direction.9

The incorporation of Taoist deities into this Buddhist temple reflects Buddhism’s strategy of associating itself with Taoism to propagate in China. To entice potential worshippers, Buddhism had to adapt to its new environment and embrace the cultural symbolism and iconography of Taoism to familiarize its foreign nature. Taoism was incorporated easily due to similarities between the Buddhist Pure Land and Taoist Heaven and the ideals of quiet and inaction seen in both ideologies.10 The Pure Land is the ideal afterlife for Buddhists – a paradise ruled by the Amitabha Buddha and a promised land for the saved in their next reincarnation.11 Taoism is also a karmic religion promoting rebirth after death, with a Heaven ruled by the Jade Emperor.12 Both religions feature a lofty spiritual goal – reaching Nirvana and achieving immortality, respectively. The Taoist idea of “wuwei” is similar to the Buddhist ideals of inaction as both emphasize following the patterns and ideals of their respective teachings.13 These similarities could be used to explain Taoism to local Chinese audiences in more digestible and accessible ways. By using the already established language and symbology of Taoism, Buddhism could more effectively communicate its values and attain followers in China.

- “Mogao Cave 249 (Western Wei Dynasty),” Dunhuang Caves on the Silk Road, accessed April 4, 2024, https://www.dunhuang.ds.lib.uw.edu/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Tan Chung and Kapila Vatsyayan, Dunhuang Art: Through the Eyes of Duan Wenjie (NewDelhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts, 1994). ↩︎

- “Mogao Cave 249 (Western Wei Dynasty),” Dunhuang Caves on the Silk Road, accessed April 4, 2024, https://www.dunhuang.ds.lib.uw.edu/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Tan Chung and Kapila Vatsyayan, Dunhuang Art: Through the Eyes of Duan Wenjie (NewDelhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts, 1994). ↩︎

- “Mogao Cave 249 (Western Wei Dynasty),” Dunhuang Caves on the Silk Road, accessed April 4, 2024, https://www.dunhuang.ds.lib.uw.edu/. ↩︎

- Yuanlin Zhang, “Dialogue Among the Civilizations: The Origin of the Three Guardian Deities’ Images in Cave 285, Mogao Grottoes,” 2009, 38. ↩︎

- “Mogao Cave 249 (Western Wei Dynasty),” Dunhuang Caves on the Silk Road, accessed April 4, 2024, https://www.dunhuang.ds.lib.uw.edu/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Anne Ning Feng, “Water, Ice, Lapis Lazuli: The Metamorphosis of Pure Land Art in Tang China,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 2018). ↩︎

- Judith A. Berling, “Taoism, or the Wa,.” Kenyon College, https://www2.kenyon.edu/Depts/Religion/Fac/Adler/Reln270/Berling-Taoism.htm. ↩︎

- Matt Stefon, “Wuwei,” Encyclopedia Britannica, September 23, 2013, https://www.britannica.com/topic/wuwei-Chinese-philosophy. ↩︎