Cave 138 – The Goddess of Childbearing Palace

The Cave Temple

Constructed during the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), Cave 138 consists of an antechamber, hallway, and main chamber. Murals adorn all three sections’ walls, ranging from donor portraits to sutras, notably the Lotus Sutra and Gratitude Sutra.1 The central altar is the most prominent and important artwork in the cave. It houses a large sitting Buddha statue, as well as multiple statues depicting the Goddess of Childbearing, her attendants, and Guanyin (the Chinese transliteration of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, and often regarded as a goddess of childbirth). The depiction of the Lotus Sutra, an important sutra for Avalokiteshvara/Guanyin, further themes this temple as a worship space for childbirth related goddesses.2

From Avalokiteshvara to Guanyin: A Case Study in the Sinicization of Buddhism

Guanyin is one of the most beloved figures in Chinese religion. It is no surprise that depictions of the bodhisattva are one of the most commonly found images at the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang.3 Furthermore, 1100 copies of scriptures related to Guanyin have been found in the Mogao cave system thus far. This includes 128 copies of the Guanyin Sutra and 860 copies of the Lotus Sutra, making it the most abundant sutra in Mogao.4 Art depicting Guanyin, such as wall paintings, banners, and hanging scrolls, exists in caves spanning from the early seventh to eleventh centuries.5

However, the Avalokiteshvara of Indian Buddhism and the Guanyin worshipped throughout China are starkly different according to the historian Chün-fang Yü, who has done extensive research on Guanyin. The most obvious difference between the two is gender – Avalokiteshvara is a male deity who occasionally takes female forms, while Guanyin is popularly depicted as a fully female goddess following the Sung dynasty.6 Avalokiteshvara is associated with royalty, whereas Guanyin is a people’s goddess who helps all, indiscriminate of status.7 Guanyin is worshipped as the Goddess of Mercy, a fertility goddess, and a protector of women and children, amongst many other roles. Cave 138 of the Mogao caves is uniquely situated temporally, as the Tang dynasty represents a major transitional era for Guanyin.8 But how did Avalokiteshvara undergo such a drastic change from India to China?

An Open Ecological Niche

Guanyin quickly became one of the most popular and revered deities in China. The swift proliferation of her worship is attributed to her uniqueness. Native Chinese theologies had no deity quite like Avalokiteshvarra. Avalokiteshvara/Guanyin was a universal savior who embodied compassion and was easily accessible to all people.9 Salvation by Avalokiteshvara/Guanyin did not necessitate studying, rituals, or status like prior philosophies – one only needed to call out sincerely.10 Avalokiteshvara/Guanyin fulfilled a religious vacuum and flourished since he/she did not need to compete with preestablished gods for followers.

Religious ecological niches explain not only the deity’s popularity, but also some of their changes. While Avalokiteshvara granted legitimacy to royalty in India, this role was already filled in China by the Mandate of Heaven.11 Guanyin’s feminization can be viewed in a similar light. As Buddhism was entering China, neo-Confucianism was becoming increasingly popular. Neo-Confucianism was a patriarchal belief system whose dominance over China’s religious landscape effectively eliminated female goddesses and ignored Chinese women’s religious needs.12 This vacuum may have contributed to Guanyin’s sexual transformation as Buddhism has often transmuted itself to fit its new host cultures’ needs.

Compassion and Wisdom: Gender Roles and Expectations

Another hypothesis for Guanyin’s feminization is differences in how ancient India and ancient China gendered wisdom and compassion. In India, Buddhist philosophy portrayed wisdom as an inferior trait inherited from the mother, and compassion as a superior trait inherited from the father.13 Therefore, Avalokiteshvara, as the bodhisattva of compassion, had to be male. However, common Chinese thought portrayed compassion as a feminine trait: “Father is strict, but mother is compassionate.”14 Guanyin then became a universal mother figure, embodying feminine virtue.

Princess Miao-shan

Guanyin also differed from Avalokiteshvara in a distinctly Chinese way – having a human origin story. While Indian Buddhism’s bodhisattvas were ahistorical, mythical beings originating in some unknown distant past, traditional Chinese religions’ deities were often historical and cultural figures with traceable roots to specific times and places.15 Guanyin conformed to this Chinese model through the legend of Princess Miao-shan.

Princess Miao-shan was the devout Buddhist daughter of King Miao-chuang. She refused marriage, so her father punished her with arduous labor at a nunnery. Incensed by Miao-shan’s continued insistence on a religious lifestyle, Miao-chuang destroyed the nunnery and killed all its inhabitants, including his daughter. A mountain spirit protected Miao-shan’s body while her soul saved those in hell. Upon returning to the earthly plane, she meditated for years to achieve enlightenment. When her father fell sick, she visited him disguised as a monk and learned he could only be saved by a medicine “concocted with the eyes and hands of someone who had never felt anger.”16 Miao-shan offered her own eyes and hands, transforming her into the Thousand-eyed and Thousand-armed Guanyin for her selfless and filial act.17

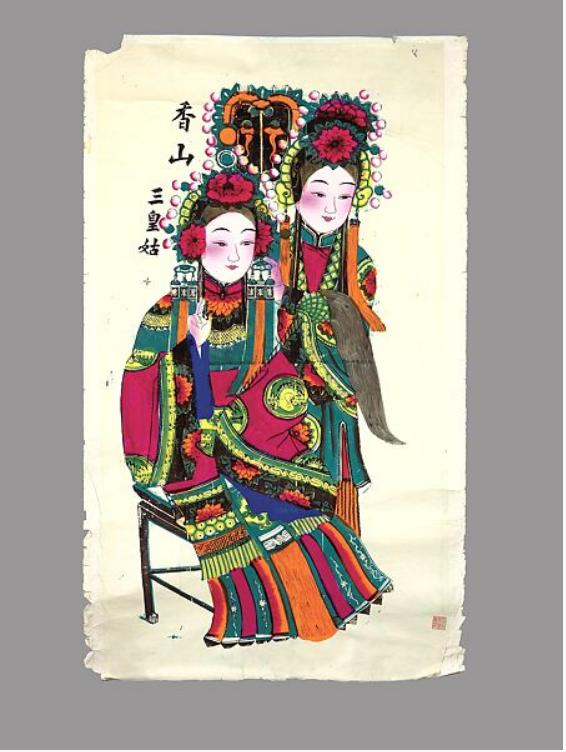

Guanyin’s new origin story lent her the same historical credence backing deities from Taoism and traditional Chinese mythology. She had a birthday and a concrete tie to a real place, Xiang-shan in the Henan province.18 Furthermore, the values expressed in the Miao-shan legend are distinctly Confucian, expressing both a virginal ideal and filial piety. Even the name Miao-shan serves to link Guanyin to a greater Chinese culture as Miao-shan was a common and popular name for Chinese girls.19 Perhaps the name was chosen intentionally for its commonality – rechristening Guanyin in an undoubtably and recognizably Chinese way. The existence and propagation of the Miao-shan legend is a powerful example of how Avalokiteshvara was altered to fit the native Chinese culture.

The Creation of Cihang Immortal

As Buddhism entered China, it interacted with local religions such as Taoism. Through linking itself with Taoism, Buddhism could gain footing in this foreign land. Guanyin exemplifies this confluence through the creation of the Buddhist/Taoist goddess Cihang Immortal.

According to Taoists, Cihang Immortal self-cultivated during the Shang dynasty and now seeks to emancipate humankind from misery.20 Taoists believe Guanyin is another name for Cihang Immortal. According to Buddhists, Cihang Immortal is the Taoist name for Miao-shan, or Guanyin, whose compassion and special assistance to women and children were noticed by Taoists.21 Cihang Immortal’s creation reflects how Buddhism adapted to and embraced the coexistence of multiple religions in Chinese culture.

The Worship of Guanyin

As a palace for the Goddess of Childbearing, this cave was likely used primarily by female worshippers seeking lucky and healthy pregnancies. According to the Lotus Sutra, women who pray to Guanyin can influence their child’s gender and attributes:

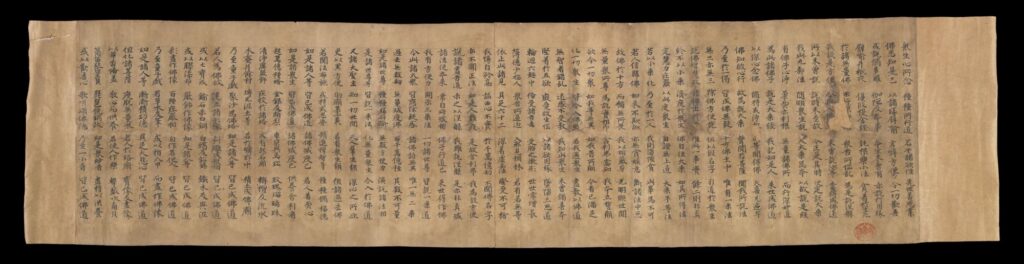

若有女人,設欲求男,禮拜供養觀世音菩薩,便生福德智慧之男。設 欲求女,便生端正有相之女,宿植德本,眾人愛敬。無盡意!觀世音 菩薩有如是力。若有眾生恭敬禮拜觀世音菩薩,福不唐捐。

Ying Huang, “Songzi Guanyin and Koyasu Kannon: Revisiting the Feminization of Avalokiteśvara in China and Japan,” Education and Research Archive (thesis, 2019), 32.

If any woman wanting to have a baby boy pays homage and makes offerings to Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, she will bear a baby boy endowed with good merit and wisdom. If she wants to have a baby girl, she will bear a beautiful and handsome baby girl who has planted roots of good merit and will have a love of sentient beings. O Akṣayamati! Such is the transcendent powers of Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara that if any sentient being reverently respects him, the merit they achieve will never be in vain.

Ying Huang, “Songzi Guanyin and Koyasu Kannon: Revisiting the Feminization of Avalokiteśvara in China and Japan,” Education and Research Archive (thesis, 2019), 32.

Touching a Guanyin statue, chanting Guanyin’s name, burning incense, and displaying Guanyin’s image were ways of worshipping Guanyin and praying for a son.22 Other common methods included donating money to Guanyin and reciting her scriptures.23 These activities could be conducted in this cave temple or in the home. The most effective days to pray to Guanyin for children were her birthday (February 19th), the anniversary of her enlightenment (June 19th), and the anniversary of the day she first left home (September 19th).24

Another method of praying to Guanyin for a son was through reciting this dharahi sutra:

The mantra that purifies the karma of the mouth: An-hsiu-li, hsin-li, moho-hsiu-li, hsiu-hsiu-li, suo-p’o-ho [svaha].

Chün-fang Yü. Kuan-yin: The Chinese transformation of Avalokiteśvara. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 126.

The mantra that pacifies the earth: Nan-wu-san-man-to, mo-to-nan, antu-lu-tu-lu-ti-wei, suo-po-ho.

The sutra-opening gatha:

The subtle and wondrous dharma of utmost profundity

Is difficult to encounter during millions, nay, billions of kalpas.

Now that I have heard it [with my own ears], I will take it securely to

heart

And hope I can understand the true meaning of the Tathagata.

Invocation:

Bowing my head to the Great Compassionate One, Po-lu-chieh-ti

Practicing meditation focused on the sense of hearing, [the bodhisattva] entered samadhi

Raising the sound of the tide of the ocean,

Responding to the needs of the world.

No matter what one wishes to obtain

[she] will unfailingly grant its fulfillment.

Homage to the Original Teacher Sakyamuni Buddha

Homage to the Original Teacher Amitabha Buddha

Homage to the Pao-yüeh Chih-yen Kuang-yin Tzu-tsai-wang Fo (Sovereign Master Buddha of Precious Moon and the Light and Sound of Wisdom Peak)

Homage to Great Compassionate Kuan-shih-yin Bodhisattva

Homage to White-robed Kuan-shih-yin Bodhisattva

Front mudra, back mudra, mudra of subduing demons, mind mudra, body mudra.

Dharahi. I now recite the divine mantra. I beseech the Compassionate One to descend and protect my thoughts. Here then is the mantra:

Nan-wu-ho-la-ta-na, shao-la-yeh-yeh, nan-wu-a-li-yeh, po-luchieh-ti, shao-po-la-yeh, p’u-ti-sa-to-po-yeh, mo-ho-chieh-luni-chia-yeh, an-to-li, to-li, tu-to-li, tu-tu-to-li, suo-p’o-ho.

When you ask someone else to chant the dharahi, the effect is the same as when you chant it yourself

The sutra was inscribed onto a statue of Guanyin in 1082. While this dharahi was mostly recited at home by both men and women, its contents suggest what women’s prayers to Guanyin at this temple might have sounded like.25

Conclusion

Cave 138 represents an important transition period in the history of Chinese religion, the phase of Guanyin’s Sinicization and gender transformation. Its altar – containing the six-armed Guanyin reminiscent of traditional Indian depictions of Avalokiteshvara standing amongst child-granting goddesses – exemplifies this transition by demonstrating that Guanyin was indeed adopted as a child-granting goddess in China. This idea is further supported by the presence of the Lotus Sutra in the cave, and perhaps by the depiction of the donor with child. Based on the art, we can speculate what types of worship may have occurred in this ritual space. Praying for children is an especially likely use. Ultimately, the cave serves as an important marker on the progress of the Sinicization of Buddhism by shedding light on the state of the Chinese perception of Avalokiteshvara/Guanyin.

- “Mogao Cave 138 (Late Tang Dynasty, Qing Dynasty),” Dunhuang Caves on the Silk road, accessed April 4, 2024, https://www.dunhuang.ds.lib.uw.edu/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Jeong-Eun Kim, “White-Robed Guanyin: The Sinicization of Buddhism in China Seen in the Chinese Transformation of Avalokiteshvara in Gender, Iconography, and Role,” n.d., 17. ↩︎

- Ibid., 17. ↩︎

- Ibid., 17. ↩︎

- Chün-fang Yü. Kuan-yin: The Chinese transformation of Avalokiteśvara. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 2, 6. ↩︎

- Ibid., 21. ↩︎

- Ying Huang, “Songzi Guanyin and Koyasu Kannon: Revisiting the Feminization of Avalokiteśvara in China and Japan,” Education and Research Archive (thesis, 2019), 2. ↩︎

- Chün-fang Yü. Kuan-yin: The Chinese transformation of Avalokiteśvara. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 21. ↩︎

- Ibid., 489. ↩︎

- Ibid., 21. ↩︎

- Ibid., 20-21. ↩︎

- Ibid., 414-416. ↩︎

- Ibid., 414. ↩︎

- Ibid., 294-295. ↩︎

- Ibid., 294. ↩︎

- Ibid., 293-294. ↩︎

- Jeong-Eun Kim, “White-Robed Guanyin: The Sinicization of Buddhism in China Seen in the Chinese Transformation of Avalokiteshvara in Gender, Iconography, and Role,” n.d., 19. ↩︎

- Ibid., 19. ↩︎

- “Mogao Cave 138 (Late Tang Dynasty, Qing Dynasty),” Dunhuang Caves on the Silk Road, accessed April 4, 2024, https://www.dunhuang.ds.lib.uw.edu/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ying Huang, “Songzi Guanyin and Koyasu Kannon: Revisiting the Feminization of Avalokiteśvara in China and Japan,” Education and Research Archive (thesis, 2019), 41. ↩︎

- Ibid., 25. ↩︎

- Chün-fang Yü. Kuan-yin: The Chinese transformation of Avalokiteśvara. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 126-127. ↩︎