Construction of Ritual and Artistic Spaces

Since their construction in the fourth century, the Mogao Caves were meticulously planned to serve as ritual spaces and a reflection of Chinese artistic history and life. Originally built as sites of meditation, the Mogao Caves would evolve, over the course of a millenium, into destinations of worship and pilgrimage through their sheer collection of Buddhist art.1 With meticulous attention to detail, these caves, ranging in the hundreds, were later built and painted by artisans with the sponsorship of rulers, merchants, and the elite.2

Initial cave construction was marked by the excavation of living rock of the Sanwei Mountain facade. In the next phase of the construction process, what were once gaping holes bored into the sides of mountains were transformed into elaborate square chambers, complete with raised, sloped ceilings finished with plaster and dried plant matter.3 These rooms were painted and constructed with much thought and precision. All roughly 500 chambers consist of a similar layout: a main chamber, antechamber, corridor, and side chambers (although some caves lack these facades due to damage overtime).4 Sculptures, often portraying religious figures and iconography, were positioned in the back of the caves on platforms that served as altars, in shelves carved into the cave walls, or on the faces of central pillars.5

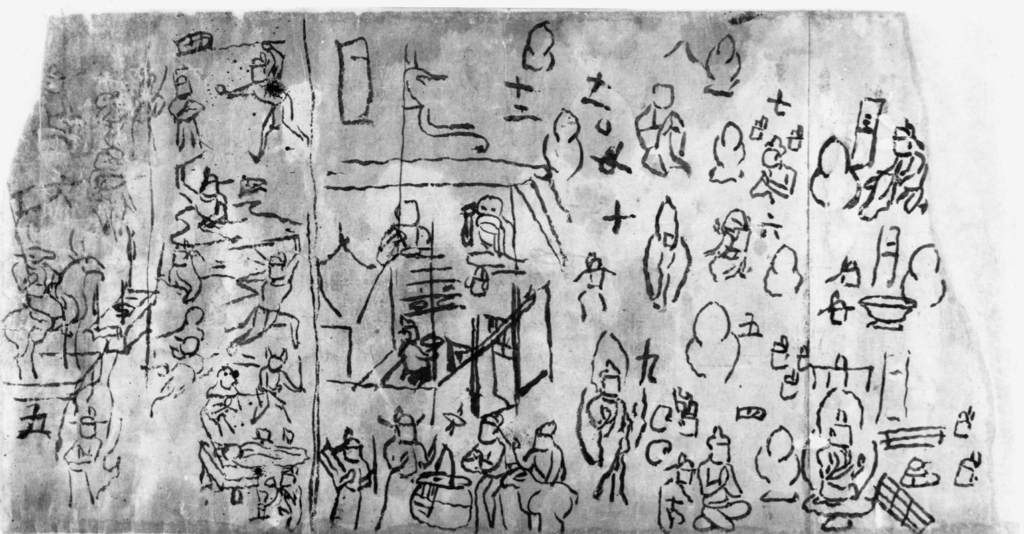

Preparatory sketches and layouts were also created before the construction of the Mogao Caves. Overlapping iconographic content, created over a period of centuries, suggests that thoughtful, organized methods were taken throughout mural and tapestry production. Such examples of painting production can be seen especially in the ninth and tenth centuries.6 In this time especially, workshops, which served the royal court and those connected to the elite, were recruited in the production of art for the Mogao Cave murals.7 Before painting began, artisans produced preparatory sketches. Much of the intent behind preparatory sketches was to determine and map out information for wall and tapestry painting. The quality and type of preliminary sketches produced by artisans varied based on the medium and purpose of the artwork. For murals, sketches consisted of abbreviated studies and schematics of walls, detailed studies of specific figures, and designs for repetitive ceiling designs. Silk works were produced to aid in the duplication of banners. Ritual sketches were utilized by monks and nuns in faith based practices, and were created with this in mind.8 Sketches, whether religious or purely artistic, began as freehanded, less detailed portrayals of structures and artwork, especially in the case of mural art. However, as the artistic process developed, sketches became more detailed until the final results were reached.

Ritual and Historical Use

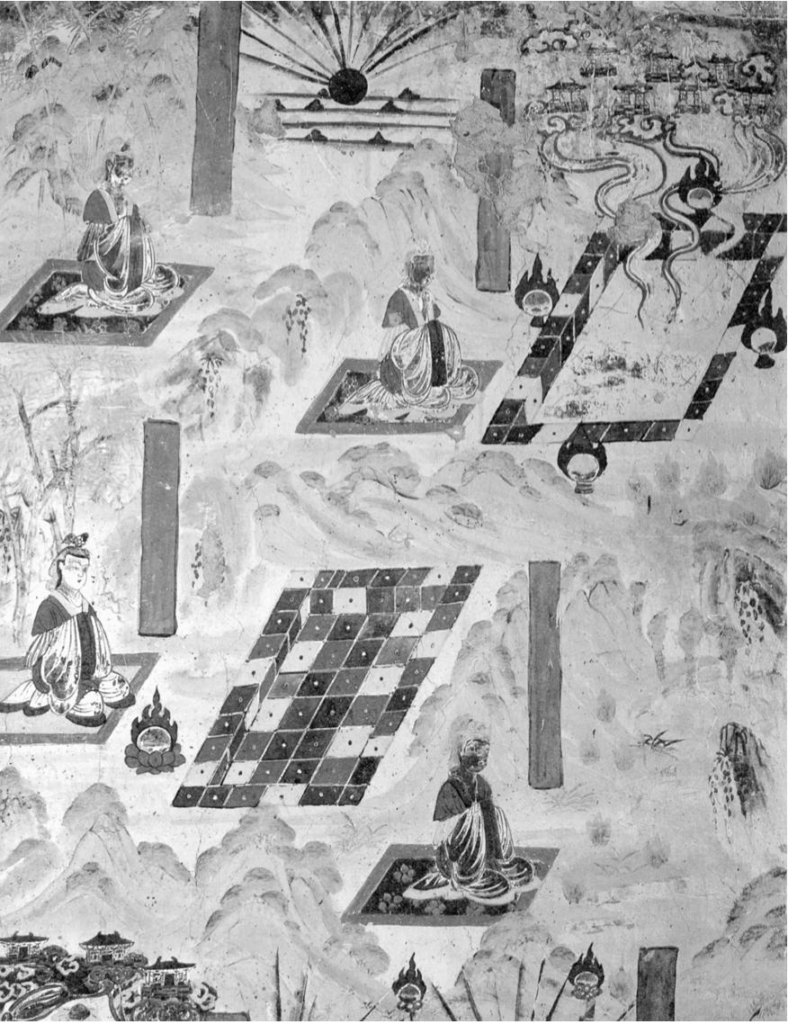

In its earliest period, the Mogao Caves were built with meditation in mind, as reflected by predominantly older grottoes. One such example of such a cave is Cave 285, whose ritualistic intentions are shown in its curation. Completed in 538 AD, murals of Cave 285 depict brightly colored celestial deities. One deity, representing gluttony in Buddhism and who consumes devils in Chinese mythology, is painted on the four corners of the room, manifesting spiritual protection for all who enter the chamber.9 Four meditation chambers are carved into the North and South walls of Cave 285, and statues of meditating Buddhas are placed into carved niches for altar worship. Thirty five paintings of meditating monks adorn the ceiling of the space as well. It is believed that visualizing the Buddha is in itself meditative in nature, thus many of these works, purely in their nature, serve to aid in the practice of meditation.10 Mountain motifs, portrayed near the painted monks on portions of the ceiling, represent the attainment of enlightenment. Other paintings replicate Buddhist stories and historical accounts, such as that of a tale portraying the salvation of punished bandits.11 Aside from Buddhist motifs, portraits of donors and their families are painted to recognize their support in the construction of the room. Male donors are dressed in nomadic clothing of the metropolitan Chinese, while female donors wear Han style clothing, suggesting cultural intersectionality and the shared practice of Buddhism that brought various groups of people together.12

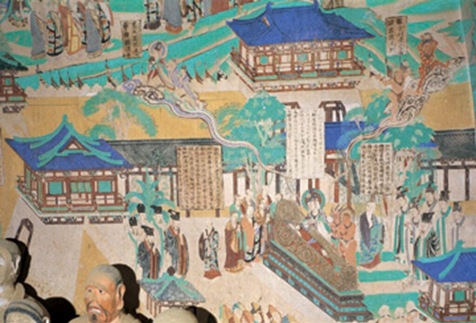

Other caves not only act as sites to conduct rituals, but to reflect the importance of stories and teachings of Buddhism. Mogao Cave 148 is an example of this. Located in the southern portion of the grotto system, Cave 148 forms the Nirvana cave. As denoted by tablet inscriptions carved in the antechamber of the cave, this space was constructed by the powerful Li Dabin family in the Tang Dynasty. It was then reconstructed in the late Tang Dynasty, the Western Xia Period, and the Qing Dynasty.13 The primary focus of Cave 148 is a massive sculpture of a resting Buddha reaching Nirvana, paired with paintings of the Nirvana Sutra transformation. Unlike other spaces in the Mogao Caves, the main chamber of Cave 148 takes on a rectangular shape with a longitudinally vaulted ceiling. The statue in the Buddhist altar in the center of the cave has a length of 14.40 meters (47 feet), making this the second largest statue in the Mogao Caves.14 Behind this gargantuan statue are smaller statues representing bodhisattvas, mons, and celestial beings, with most being constructed in later years. Paintings surrounding the statue portray the Nirvana sutra in massive strips, with murals reaching heights of 2.5 meters (8 feet) and lengths of 23 meters (75 feet).15 These paintings include 10 scenes, 66 storylines, and more than 500 characters and animals, and are the largest painting of the Nirvana sutra in the Mogao Caves as a result. The composition of the paintings are incredibly vivid and colorful, with magnificent landscapes and architecture. It also includes 66 inscriptions in ink, providing historical context for interpretation. Other sutras, including the “Medicine Buddha Sutra” are painted along the east wall of the cave in equally extravagant fashion.16 Paintings like the “Gratitude Sutra” and “Devata Sutra” are scenes that first appeared in this cave among the Mogao Grottoes, and were imitated in caves built in later dynasties.17 The grandeur of this room reflects the importance of Nirvana, or the highest attainment, in Buddhism, and the weight of their importance among the altars in the Mogao Caves.

While many grottoes in the Mogao Caves are utilized for exclusively ritualistic purposes, others intertwine religious and historical elements. The most prominent example of this case is Mogao Cave 17, otherwise known as the Library Cave. Built during the Dazhong and Xiantong periods of the late Tang Dynasty (851-862 AD), this cave was constructed to serve as a memorial for Dunhuang’s chief monk, Hong Bian, whose likeness is captured in a bright eyed statue bordered by banyan trees and paintings of his attendants.18 While the exact reasons remain unknown, more than 50,000 relics spanning from the fourth to eleventh century, consisting of Buddhist scriptures, educational and medicinal manuscripts, ritualistic musical instruments, paintings, and other documents were hidden in Cave 17 in the eleventh century.19 A painted wall was placed over the entrance of the cave, leaving it sealed until 1900, when it was discovered accidentally by a Taoist priest.20 This discovery was pivotal in the understanding of the scope of the Mogao Caves. Not only were the Mogao Caves used for ritual purposes, they also kept detailed historical records which reflected the extensive cultural interactions observed at Dunhuang as a central location along the Silk Road. Literature written in texts belonging to several groups, including Kucha, Sogdiana, Sanskrit, Turkik, Tibetan, Uighur, and Khotan were discovered with written Chinese texts.21 Artifacts spanning over multiple dynasties suggest the intention of preservation, with Cave 17 acting as a vessel whose purpose is to capture time.

Contemporary Curation and Conservation

It was the discovery and subsequent excavation of the library caves that brought the Mogao Caves back into consciousness. After being hidden for nearly a thousand years, the Mogao Caves were left in ruins. Desert sands and winds eroded cliffs and the caves built within them. Mineral deposition altered and warped elaborate murals. Excavation and later theft of artifacts destroyed and separated artifacts from their home.22

Despite its recognition as a cultural icon and its extensive damage, the Mogao Caves did not receive proper maintenance until the 1940s, largely due to political changes and wars during this time. It was this change that prompted the curation and management of the Mogao Caves and the recognition of its significance as a major historical and cultural beacon.23 This led to the conservation of its shrines, and its acknowledgement as a prominent tourist destination.

Curation of the Mogao Caves does not only focus on conservation. In recent years, curation has evolved into organizing exhibitions that can be observed on a global scale. This has included physical, but also digital exhibitions. In 2016, the Getty Center, located in Los Angeles, orchestrated an elaborate exhibition in order to give those living outside of China an opportunity to view the splendor of the Mogao Caves.24 Through art loaned from museums such as the British Museums and the Mogao Caves themselves, as well as videos, virtual tours, photographs, and elaborate cave replicas, the exhibition was able to successfully immerse tourists and tell the story of the Mogao Caves: their creation, encounters with destructive threats from nature and humans, and the immense efforts in place to aid in conservation and protect the caves for future generations.

One prominent organization that relies on digital platforms to curate the Mogao Caves is the Dunhuang Foundation. Powered by support from the University of Washington’s Tateuchi East Asia Library, the Dunhuang Foundation is a digital exhibition detailing the rich history of the Mogao Caves. Each subpage on the website is equipped with in-depth descriptions and research, as well as high quality images of art and the caves themselves. The site also has virtual exhibitions that immerse visitors through their devices.

- Dunhuang Foundation. “Dunhuang Videos 敦煌影像.” Dunhuang caves on the silk road: Online Exhibitions & Speaker Series 丝路上的敦煌石窟: 虚拟展览及演讲系列. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.dunhuang.ds.lib.uw.edu/extended-readings/. ↩︎

- Fraser, Sarah Elisabeth. Performing the visual: The practice of Buddhist wall painting in China and Central Asia, 53. Stanford (Calif.): Stanford University Press, 2004. ↩︎

- Fraser, Sarah Elisabeth. Performing the visual: The practice of Buddhist wall painting in China and Central Asia, 48. Stanford (Calif.): Stanford University Press, 2004. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Fraser, Sarah Elisabeth. Performing the visual: The practice of Buddhist wall painting in China and Central Asia, 54. Stanford (Calif.): Stanford University Press, 2004. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Dunhuang Foundation. “Dunhuang Videos 敦煌影像.” Dunhuang caves on the silk road: Online Exhibitions & Speaker Series 丝路上的敦煌石窟: 虚拟展览及演讲系列. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.dunhuang.ds.lib.uw.edu/extended-readings/. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Dunhuang Foundation. “Mogao Cave 148 (High Tang Dynasty).” Dunhuang caves on the silk road: Online Exhibitions & Speaker Series 丝路上的敦煌石窟: 虚拟展览及演讲系列. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.dunhuang.ds.lib.uw.edu/mogao-cave-148-high-tang-dynasty/. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Dunhuang Foundations. “Mogao Cave 17 – The Library Cave (Late Tang Dynasty).” Dunhuang caves on the silk road: Online Exhibitions & Speaker Series 丝路上的敦煌石窟: 虚拟展览及演讲系列. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.dunhuang.ds.lib.uw.edu/mogao-cave-17-the-library-cave-late-tang-dynasty/. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Reed, Marcia. “The Mogao Caves as Cultural Embassies.” Harvard Divinity Bulletin, May 7, 2016. https://bulletin.hds.harvard.edu/the-mogao-caves-as-cultural-embassies/.

↩︎ - “Conservation and the Future of Dunhuang.” Omeka RSS. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://dunhuang.ds.lib.uw.edu/Dunhuang-Exhibitions/exhibits/show/conservation/introduction.

↩︎ - Reed, Marcia. “The Mogao Caves as Cultural Embassies.” Harvard Divinity Bulletin, May 7, 2016. https://bulletin.hds.harvard.edu/the-mogao-caves-as-cultural-embassies/. ↩︎